Jurors knew Samsung was guilty after first day of deliberations, wanted to send message with verdict

In a pair of reports from Reuters and CNET, jury foreman Velvin Hogan and juror Manuel Ilagan described what went on behind closed doors as the nine-member group deliberated the landmark verdict.

Apple on Friday was awarded nearly $1.05 billion after Samsung was found to have infringed on six of seven asserted patents, while the Korean company won none of their counterclaims.

The one-sided victory for Apple came quickly, as the jury took only 21 hours, or less than three working days, to come to a consensus after counsel spent three weeks presenting arguments and testimony.

Ilagan told CNET the jury was convinced of Samsung's guilt after only one day of deliberations, noting that the seemingly fast verdict was carefully decided after weighing evidence presented by both parties. Altogether, the group had to decide on over 700 questions related to patents and patent rights.

"We weren't impatient," Ilagan said. "We wanted to do the right thing, and not skip any evidence. I think we were thorough.We found for Apple because of the evidence they presented. It was clear there was infringement."

Foreman Hogan echoed the juror's sentiment, telling Reuters that video testimony from Samsung officials made it "absolutely" clear that the company willfully infringed on Apple's trade dress. He went on to say Apple's arguments for the protection of intellectual property factored largely into the jury's decision.

"We didn't want to give carte blanche to a company, by any name, to infringe someone else's intellectual property," Hogan said.

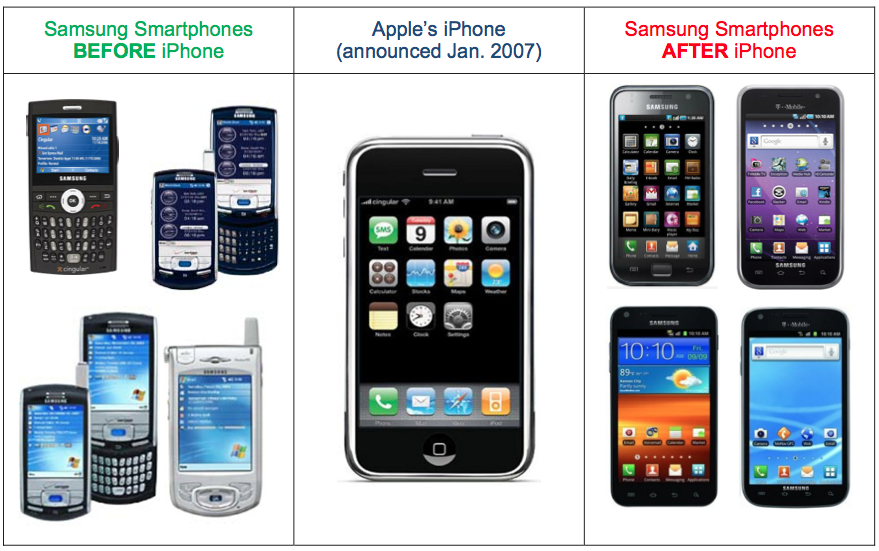

Also factors were a number of internal emails Samsung executives sent to each other regarding features seen on the iPhone, as well as a demonstrative exhibits showing the evolution of the Korean company's phones before and after Apple's handset was released.

As for Samsung's claims of infringement, Ilagan said the company lost the jury when it tried to leverage two UMTS wireless patents against Apple, one of which involved the communications chip in the iPhone and iPad. Apple refuted this specific claim and pointed to a Samsung licensing deal with Intel, the maker of the iDevice chips. The agreement stated that Samsung was not allowed to sue any company to which Intel sold that particular component, a licensing safeguard known as patent exhaustion.

In going through deliberations, jurors had trouble with prior art Samsung counsel presented to counter Apple's patent claims, including the '381 "rubber-banding" and '915 "pinch-to-zoom" patents. Ilagan noted that Hogan, who had been part of a jury three times before, was familiar with patents as he owned a number himself, making the foreman an invaluable asset in navigating the murky waters of invention claims.

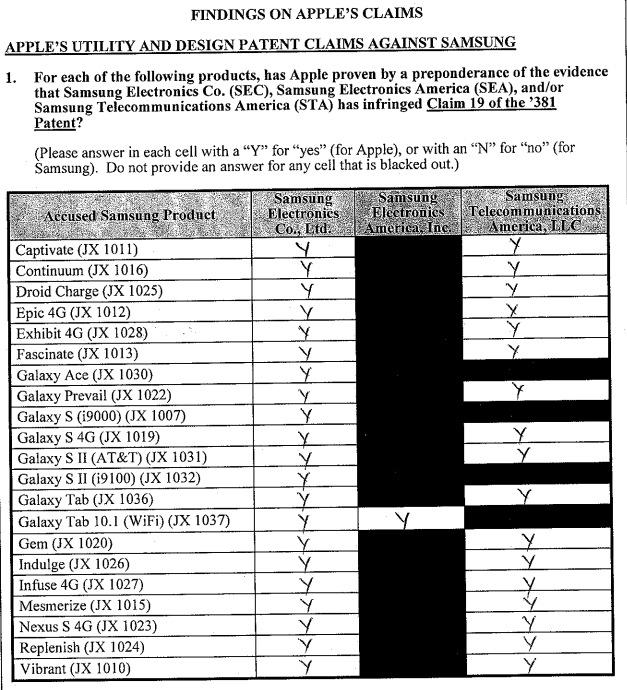

After it was decided that Samsung was guilty of infringement, Ilagan said it was easy to determine which handsets were in violation.

"Once you determine that Samsung violated the patents, it's easy to just go down those different [Samsung] products, because it was all the same," Ilagan said. "Like the trade dress — once you determine Samsung violated the trade dress, the flat screen with the Bezel...then you go down the products to see if it had a bezel. But we took our time. We didn't rush. We had a debate before we made a decision. Sometimes it was getting heated."

After the infringing products were tallied, damages were assigned based on numbers the jury thought was fair but substantial. Apple claimed Samsung enjoyed 35.5 percent profit margins from selling the infringing products, but the jury disagreed and offered a calculation more in line with the Korean company's claim of 12 percent margins.

"We wanted to make sure the message we sent was not just a slap on the wrist," Hogan said. "We wanted to make sure it was sufficiently high to be painful, but not unreasonable."

When asked if the jury knew just how significant the Apple v. Samsung trial was, Ilagan said, "I realized that's a big deal if Samsung can't sell those phones, but I'm sure Samsung can recover and do their own designs." He went on to say, "There are other ways to design a phone. What was happening was that the appearance [of Samsung's phone] was their downfall. You copied the appearance…. Nokia is still selling phones. BlackBerry is selling phones. Those phones aren't infringing. There are alternatives out there."

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen