Samsung copies Apple's claims it destroyed email evidence in "me too" filing

In opposing the motion, Apple's attorneys twice referred to Samsung's motion as a "me too" filing, according to a report discussing the situation by FOSSPatents writer Florian Mueller.

Apple's filing further revealed that the company "negotiated with Samsung in good faith after first apprising Samsung of its infringement claims" in the summer of 2010 and sued "only after Samsung announced a new round of infringing products in Spring 2011.

"Samsung made clear to Apple that it would not stop copying Apple's products."

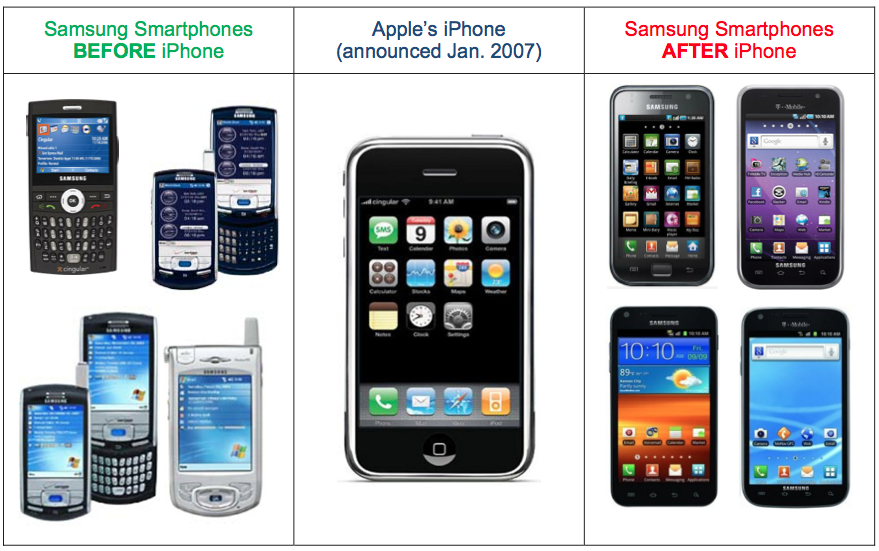

Apple illustration of Samsung phones pre- and post-iPhone. | Source: Apple trial brief

Apple's original motion for an adverse inference jury instruction

Apple's motion for an "adverse inference jury instruction" is based on the fact that Samsung's email system was designed to routinely destroy emails after two weeks, and that Samsung did not follow legal obligations to retain potential evidence.

The motion Apple filed took issue with "whether Samsung took adequate steps to avoid spoliation after it should have reasonably anticipated this lawsuit and elected not to disable the auto delete function of its homegrown 'mySingle' email system."

Apple also cited the fact that Samsung had previously been found, in the Mosaid v Samsung case from seven years ago, to have similarly maintained policies that "resulted in the destruction of relevant emails" in that case, resulting in "the imposition of both an inverse interference and monetary sanctions" against it.

Rather than changing its behavior, Apple outlined that Samsung took no action to preserve evidence from automatic deletion even though litigation was "reasonably foreseeable."

Magistrate Judge Paul S. Grewal responded to the motion by stating that Samsung had "consciously disregarded" its legal obligations, and ordered that the jury hearing the case be advised:

"Samsung has failed to prevent the destruction of relevant evidence for Apple's use in this litigation. This is known as the 'spoliation of evidence.'

I instruct you, as a matter of law, that Samsung failed to preserve evidence after its duty to preserve arose. This failure resulted from its failure to perform its discovery obligations.

You also may presume that Apple has met its burden of proving the following two elements by a preponderance of the evidence: first, that relevant evidence was destroyed after the duty to preserve arose. Evidence is relevant if it would have clarified a fact at issue in the trial and otherwise would naturally have been introduced into evidence; and second, the lost evidence was favorable to Apple.

Whether this finding is important to you in reaching a verdict in this case is for you to decide. You may choose to find it determinative, somewhat determinative, or not at all determinative in reaching your verdict."

Mueller reported that "for an adverse inference jury instruction, this is relatively soft. The court could also have told the jury that it "must" presume that relevant evidence in Apple's favor was lost, or in a worst-case scenario for Samsung, that certain of Apple's claims must be deemed proven."

At the same time, the order "doesn't make Samsung look good, generally speaking," Mueller observed, adding that "this evidentiary issue is particularly relevant is the question of whether Samsung willfully infringed on Apple's intellectual property."

Samsung copies Apple's email destruction claim

Following the order granting Apple's motion, Samsung filed its own accusations that Apple too failed to preserve email evidence, which Apple contested on the grounds of being "untimely" as it was filed just two days before trial.

In his report covering Samsung's counter motion asserting similar claims, Mueller flatly said that Samsung's "motion makes no sense whatsoever."

Among the differences between the filings by Apple and Samsung are the facts firstly, Apple doesn't routinely and automatically delete its emails as a matter of policy.

"There is an enormous difference between systems like Samsung's that require individuals to 'opt in,' by taking affirmative actions to preserve [relevant messages], and systems like Apple's that require individuals to 'opt out,' by taking affirmative actions to delete," Apple stated in its brief opposing Samsung's motion.

Secondly, Apple was already involved in patent lawsuits involving Nokia, HTC and others, and therefore was already following evidence retention rules. Samsung is accused of taking no steps to preserve evidence despite knowing that litigation was reasonably foreseeable.

Thirdly, while Apple has identified some email evidence supporting its claim that Samsung willfully infringed, leaving it reasonable that there was additional supporting evidence available, Samsung's accusations are not based on any "showing of harm."

Mueller noted that Apple's filing stresses "that Samsung's motion doesn't provide any indication that relevant emails (that would have helped Samsung's case) got lost."

Instead, Samsung argued it only received 66 emails from Apple pertaining to patents during the August 2010 to April 2011 period, suggesting that there should be more evidence to comb through.

"Apple produced zero Steve Jobs e-mails from the key August 2010 to April 2011 period (and 51 e-mails overall from Jobs)," Samsung's motion argued.

"The company received 9 e-mails from Mr. [Jonathan] Ive (45 overall) from that period. These are absolutely critical witnesses — it is inconceivable that Mr. Jobs, CEO of Apple during a portion of the relevant time period and inventor of the '949, '678, D'087, D'677, D'270, D'889, D'757 and D'678 patents, actually had so few e-mails on issues in this case and none between August 2010 and April 2011."

Reflect, distract, simplify

Mueller writes that "Samsung's tactics make psychological and political sense. It seeks to capitalize on the fact that the court (as well as the appeals court) will want to avoid any impression of double standards."

Before filing its own motion, Samsung initially insisted that Apple's award of an adverse inference jury instruction must be reversed by the court lest it "undermine the fairness of the trial and ensure that any verdict in Apple's favor must be reversed."

After failing to get the order overturned, Samsung filed its own accusations against Apple, alleging the potential of missing email evidence, an apparent effort to water down the seriousness of its own apparently intentional efforts to allow evidence to be destroyed with the claim that both parties were essentially equally guilty.

Samsung's filing simply insists that "without question, documents that Apple destroyed contained product comparisons and admissions that should have been preserved and produced for Samsung's use in this case."

Reductio ad absurdum

Samsung's countersuit over patent infringement employs the same tactics, creating the suggestion that both companies were equally guilty of "patent infringement," blurring black and white issues into a muddy pool where observers can see whatever they want to see.

Samsung has been particularly effective in reducing Apple's design patent infringements down to the suggestion that Apple is suing over "rectangles," a talking point often repeated to sympathetic media sources by Samsung's chief product officer Kevin Packingham.

"Consumers want rectangles and we’re fighting over whether you can deliver a product in the shape of a rectangle," Packingham insisted, adding that Samsung also has design patents of its own that are "not as simple as the rectangle."

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard