Inside OS X 10.8 Mountain Lion: a Preview of how Apple is enhancing the file system with iCloud

iCloud was a top billed feature of OS X 10.7 Lion, replacing MobileMe and adding Photo Stream, Find My Mac and early support for Documents & Data.

In Mountain Lion, iCloud adds new support for configured Accounts sync between systems, and enhances Back to My Mac with automated troubleshooting fixes. As pictured below, iCloud's System Preferences pane now offers to automatically enable NAT Port Mapping Protocol on your AirPort base station to make sure BTMM will work as intended.

The evolution of iCloud

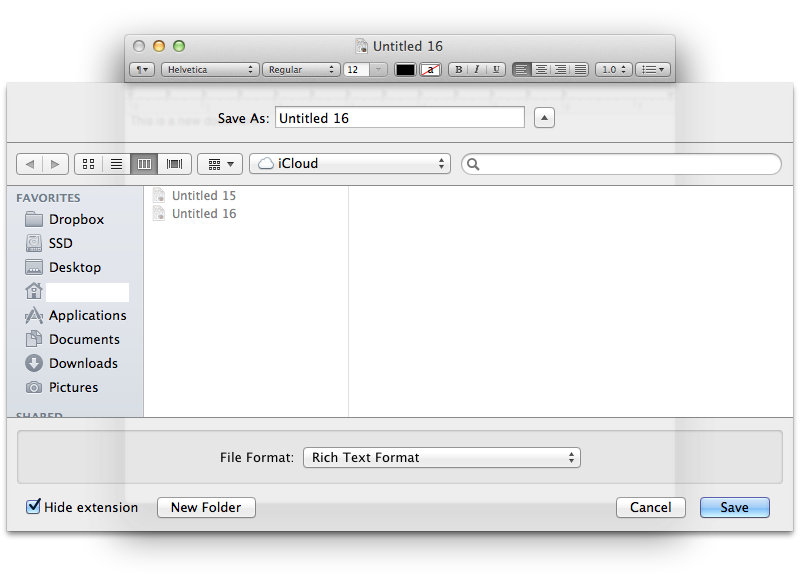

Prerelease builds of Mountain Lion indicate Apple has been experimenting with how to add iCloud features to its own apps, including the simple Text Edit. Initially, iCloud was simply added as the default location for new files (if a user was signed into the service). When you save a Text Edit document, iCloud appears as an alternative location, despite being nowhere on the real local file system.

This behavior is similar to how iDisk worked, and also similar to using a remote file server. Among other Mountain Lion apps however, support for iCloud is far more sophisticated and simplified, with a strong resemblance to iOS. A key example of how it works is visible in Preview.

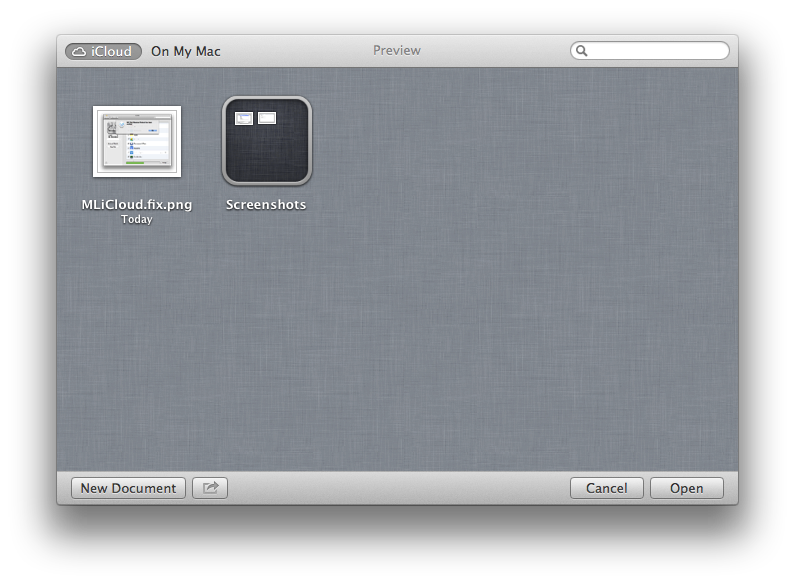

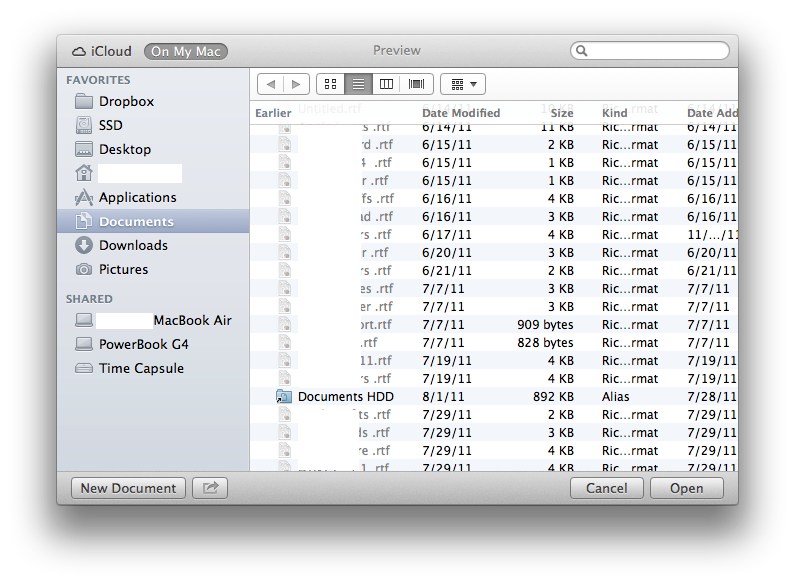

Preview not only shows off how Apple is rethinking the toolbar, it also demonstrates how the company wants apps to access documents saved to iCloud. In the open file dialog below, Preview presents two options: the default, graphical iCloud window showing files in Preview's App Library of documents saved on iCloud (below top), and the standard file system available by clicking On My Mac (below bottom).

You can add files to Preview's iCloud App Library by dragging them into the iCloud open file window from the Finder or desktop. You can also organize documents into iOS style Folders, which work the same way, as shown below.

ICloud is more than remote storage

While often compared to Dropbox, Microsoft SkyDrive or other cloud storage services, iCloud is a package of unique offerings that goes far beyond offering just web-based file storage. Apple introduced iDisk for Mac users back in 2000, allowing simple remote internet storage of files. There's nothing new about that.

One major new difference with iCloud it that ties documents with their application. This is similar to how iOS stores apps' files within the apps' own sandbox. When iOS or Mac apps save files to iCloud, they're similarly protected within that app's private library of documents.

This prevents rogue apps from accessing, erasing or modifying your data. While viruses aren't a problem for Macs today, there is malware users can inadvertently install on their own or be tricked to open. Without the kind of app-level security iCloud provides, these could damage or spy on your data.

In that sense, iCloud offers apps' documents a new level of security from other, potentially dangerous apps similar to the way file permissions work on a user level to protect all of a user's files from other, potentially dangerous users who might access the system (including a remote attacks).

On page 2 of 2: The opposite of OpenDoc, Saved in the cloud incrementally

The opposite of OpenDoc

Apple's trend toward making apps the center of the iOS and OS X experience is a reversal of the OpenDoc strategy that emerged in the early 1990s, which sought to replace big applications with software components that could be used together to edit a new type of "component document." That strategy intended to make the document itself the center of the computing world, breaking apps down into bits of functionality that could be used together to perform more complex tasks.

OpenDoc was conceptually and technically complex. Users didn't really understand the point, and many developers saw it as a lot of work that would end up replacing their apps with a bunch of individual functional components that would be more difficult to sell. Apple's 1995 mandate that its Claris subsidiary adopt OpenDoc appeared to be a major reason behind Claris' subsequent failure. OpenDoc failed to gain traction anywhere and was eventually scuttled by Steve Jobs after he returned to lead Apple in 1997.

The idea of the app (instead of the document) being the central hub for computing users' activities had already long been evident with "killer apps" such as the Apple II's VisiCalc in the 1970s and the original Macintosh's desktop publishing software of the 1980s, both well known examples of profitable and successful models for selling both computers and software.

With the rise of iOS in the 2000s, Apple worked hard to make mobile apps into the same type of high volume business as iTunes songs, a model it subsequently brought to the Mac desktop last year. These new App Store apps introduce a couple of new technologies that are the opposite of what OpenDoc aspired to achieve.

First, iOS apps are sandboxed (and Mac apps are working in that direction). This enables an app-level security that protects users' data from other apps, including when they're stored remotely on iCloud. They're no longer just thrown in a cloud storage folder like iDisk; iCloud stores each app's files in a separate sandbox, so that only that app (or a trusted companion app, or a mobile/desktop version of the app) can access it.

Apps can still export their documents and files for use with other apps, but the default behavior protects the documents you create from being maliciously or even accidentally erased, modified or spied upon by apps that shouldn't be snooping or changing things. This addresses the very real threat of malware, as opposed to the fanciful solutions to non-problems that OpenDoc was aiming to fix.

The value of iCloud is so obvious that Apple's latest ad for the iPhone 4S demonstrates its usefulness without even providing an explanation via voice over.

Saved in the cloud incrementally

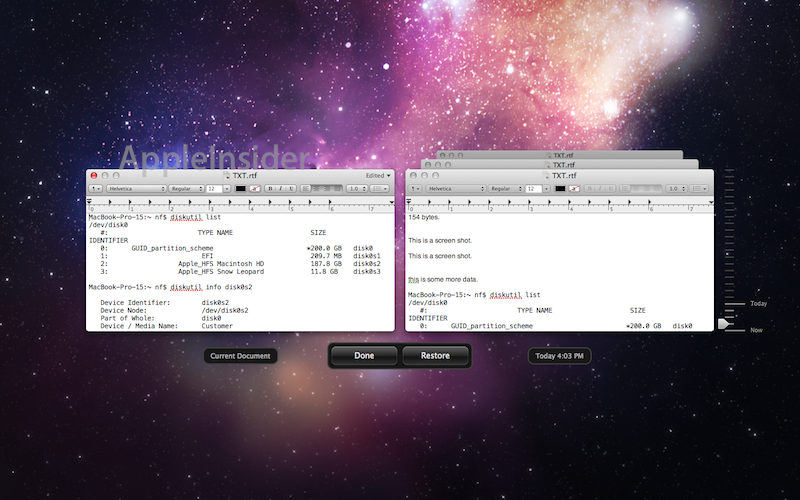

Another distinct feature of iCloud apps' documents under Mountain Lion is an extension of the Auto Save and File Versions features Apple introduced in OS X Lion last fall.

Apple now makes it easy for developers to automatically save every change to a file as you make it, allowing you unlimited undo capabilities (in Lion's Versions, below) that work similar to Time Machine, except on the scale of a single document rather than the whole file system.

When developers tap into iCloud, this autosave behavior happens automatically, efficiently saving small batches of edits rather than having to remember to initiate a "save" and then wait for it to complete. This is also how local documents are handled in iOS. The other advantage to doing this is that it will allow developers to create apps that can edit files from both Macs and iOS devices. Apple isn't quite there yet with its own iWork apps (currently iCloud support is limited to iOS apps), but Mountain Lion will eventually support an iCloud-enabled version of apps (including iWorks) to share their edits between both platforms.

iOS is ahead of the game in accessing iCloud because Apple built support for these features from scratch. On the Mac, there are already established ways to work with files, making it a challenge to introduce a simpler, smarter, easier to use system that doesn't take away features users are already accustomed to using.

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

52 Comments

This really sounds awesome for the average home user, while still retaining functionality for pro users who want more control.

For business use though, I still will prefer Dropbox. I like the philosophy of having local copies saved on each machine, in addition to in the cloud. While it may be redundant, storage is cheap and it makes it pretty much disaster-proof. Very important for critical data.

I'm assuming iCloud files aren't really on your machine, only in the cloud.

For business use though, I still will prefer Dropbox. I like the philosophy of having local copies saved on each machine, in addition to in the cloud. While it may be redundant, storage is cheap and it makes it pretty much disaster-proof. Very important for critical data.

I'm assuming iCloud files aren't really on your machine, only in the cloud.

that's where you are wrong buddy, iCloud saves the files on the cloud as well as on the registered device.

i like the way where it is going right now.

This really sounds awesome for the average home user, while still retaining functionality for pro users who want more control.

For business use though, I still will prefer Dropbox. I like the philosophy of having local copies saved on each machine, in addition to in the cloud. While it may be redundant, storage is cheap and it makes it pretty much disaster-proof. Very important for critical data.

I'm assuming iCloud files aren't really on your machine, only in the cloud.

I get the feeling that the documents exist in the machine that created or last edited it AND in the iCloud. So, if you see a document on your device that was saved somewhere else, AND you click on it, it is then on your device too, and ready to be edited.

I am a bit perplexed at how this all works though: If more then one device can see a document, how does Apple prevent various users from attempting to edit that document at the same time and not end up with a mess of versions, none of which contain all changes?

I love to see iCloud grow up. But the challenge will be to make it really simple and useful without being confusing. At the moment for instance, photo stream doesn't quite cut it. The fact that I can't control it, image by image, is frustrating.

I love to see iCloud grow up. But the challenge will be to make it really simple and useful without being confusing. At the moment for instance, photo stream doesn't quite cut it. The fact that I can't control it, image by image, is frustrating.

i agree for the photo stream part with you, the fact that i can see the fabric designs on my tv and not be able to delete them is horrible.