Microsoft uses adware model to pay for Zune HD apps

Rather than trying to seed third party developer interest organically, as Apple did when opening its iPhone App Store last summer, Microsoft's Zune Marketplace plans to create its own mobile library in house, or in conjunction with select partners, an approach closer to Apple's initial experiments with 5G iPod Games.

But instead of aiming toward building a store that encourages a wide variety of low priced software titles that can sell in high volume, Microsoft's software strategy for the Zune HD banks on delivering free software titles supported by a heavy dose of uninterruptible advertising.

Ad placement in mobile software

Apple allows App Store developers to market both free and paid apps, and the cost of developing free titles are often supported by banner ads managed by third party advertisers such as AdMob. Microsoft has been buying banner ad placement in certain iPhone apps in order to promote its Windows Mobile Marketplace, for example.

Microsoft's Zune software doesn't rely on ad banners however; it injects full screen ads that play as the apps load. More accurately, the ads play before the app loads, meaning that they can result in injecting a fifteen to thirty second delay in app startup.

A video posted by Zune HD reviewers at Ars Technica shows the Zune HD's simple Chess app taking nearly 30 seconds to load, thanks to a full video screen ad that plays before, not during, the app loading process, consuming nearly 20 seconds itself, the length of a regular TV ad. "Dang. That's all kinds of ridiculous," one viewer commented, with another adding, "That's absurd."

Who pays for software development?

The iPhone App Store's success is commonly taken for granted today, but it follows many years of failed attempts to successfully sell mobile software. Efforts by Palm, Microsoft, and Symbian to encourage the development of third party software for their mobile platforms, much like Apple's early 90s attempt to market the original Newton MessagePad, largely just copied the desktop PC software model of letting developers ship retail boxes of software on their own. The result was less successful than the PC desktop, with generally poor quality and often unfinished software titles available at only relatively high prices.

The reason: most consumers don't recognize the value of software, whether the "software" is code, music, or video. This has resulted in a combination of widespread piracy and higher software prices designed to make the honest minority pay to fund development efforts. This problem has been particularly bad for mobile devices, where simpler software titles can rarely fetch a high price from anyone, resulting in little incentive to create useful apps, lots of unfinished or low quality software, and plenty of unrealized potential for mobile platforms.

The most successful efforts at selling software often tie the abstract concept of software to a hardware medium that discourages casual piracy or unauthorized duplication, such as the CD (until the advent of easy CD burning), DVD, and various software copy protection systems such as hardware dongles or activation procedures, like those used by Microsoft to tie a Windows or Office software license to a specific PC. Prior to the iPhone, the most successful mobile software businesses were related to gaming, where software is bound to a cartridge (like the Nintendo DS) or disc (like the Sony PSP).

New models for mobile software development

For the iPhone, Apple introduced a software downloads store that tied titles to the user's iTunes account using FairPlay DRM. Yet rather than trying to extort huge sums of money from its managed software platform, the company instead aimed prices low to create a vibrant software marketplace. Apple kicked things off with an expectation-setting release of the in-house Texas Hold Em game for $5 and later offered its Remote app for iTunes and Apple TV for free. Apple has also delivered a free iDisk app tied to its MobileMe service.

The most straightforward model for supporting mobile software is paid apps, which typically cost between $0.99 and $9.99, with most apps falling in the "buck or two" category. Developers earn revenues on high volume sales, allowing users to a wide variety of quality software at a low price. Apple has encouraged developers to set a low but sustainable price on their apps. In iPhone 3.0, the company added support for in-app purchases, which enables developers to offer additional content bundles at similar "impulse buy" prices.

Apple has also promoted two types of free apps. The first, like it own Remote and iDisk apps, serves as a advertisement in itself, adding value to another product or service. A variety of companies have jumped to create free mobile apps that promote their service (such as Facebook or banking apps) or product (such as simple games that involve a brand). A second set of free apps use ad banners, following a support model commonly used on the web. Contextually sensitive banner ads sometimes have comical results, such as when ads mingle with user created content (below, the free Reddit app).

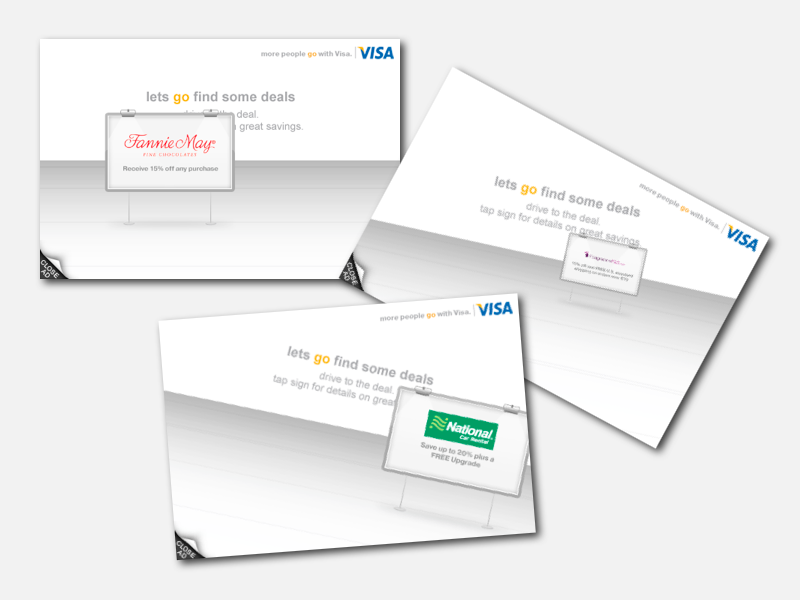

Efforts to find new ways to capture users' attention have resulted in some free iPhone apps experimenting with more prominent interstitial ads, souped up with gaming interaction features. One example is a iPhone ad campaign for Visa which puts the viewer in the role of a driver, with accelerometer-based tilt controls that allow them to steer toward offers on animated billboards. That ad still allowed viewers to bypass the ad by clicking on a close button on a dogeared corner of the screen.

Customers veto heavy adware on the web

Web advertisers discovered long ago that confronting users with ads they could not escape from— in the model of TV— didn't result in passive ad viewers, but in angry customers who simply avoided ad-heavy websites altogether. While TV viewers might budget an hour to watch a show and have grown to accept that their hour will be peppered with ads, web users with no sense of a specific time investment are often quickly outraged by ads that consume even seconds of their browsing experience, particularly ones that block their view of the content they are searching for. Some users even install software to block the banner ads that usually only appear on the periphery of the page.

A backlash against aggressive, in-your-face graphical web advertising banners promoted by Yahoo and Microsoft in the late 90s resulted in an opportunity exploited by Google: subtle, textual ads that had some relevance to the content the user was viewing. Overture, the company that invented Google's successful ad placement model, ended up disgraced by its association with the trashy Gator adware; Yahoo's acquisition of Overture in 2003 further differentiated the line between the classy and subtle adware of Google with the more overt adware models pushing annoying and sometimes offensive popup ads.

After initially dabbling in ad banner placement to support its Sherlock web search app a decade ago (below), Apple has staunchly avoided ad-centric models for supporting its own development efforts. Unlike most competitors, iTunes is completely devoid of any overt advertising. Content Apple sells in iTunes is all ad-free, in stark contrast to the TV-style ads that are used in competing efforts to support the display of content on the web, such as Hulu. Apple's free and shareware-priced applications, whether for the Mac, iPhone, or Windows, have all opted against any sort of ad placements.

Microsoft's soft spot for adware

Microsoft has long taken a different approach. A decade ago, Microsoft lined up prominent advertising on the Windows 98 desktop (below), and Windows PCs have become increasingly glutted with adware loaded by vendors and partners ever since. Ignoring the fall of Overture, Microsoft actually entered talks to acquire purchase Claria, the vendor behind the notorious Gator and its adware network that provided "ad support" for apps like the music sharing Kazaa service, installing a plague of popups. During negotiations, Microsoft reclassified Gator from adware that needed to be quarantined to a benign, reputable product users should embrace.

In 2004, the WinCE-powered Gametrak, later renamed Gizmondo, tried to market a handheld game console for either $400 or $229 loaded with push advertising. in 2005, Microsoft researchers wrote a report stating, "As Web advertising grows and consumer revenues shrink, we need to consider creating ad-supported versions of our software," according to an article by Ina Fried of CNET.

Fried's article also cited contemporary memos written by Microsoft's Chief Technical Officer Ray Ozzie, which stated that Microsoft had an obligation to act on the shift to ad-supported software. "It's clear that if we fail to do so, our business as we know it is at risk," Ozzie wrote. "We must respond quickly and decisively."

Earlier this year at the Morgan Stanley Technology conference, Microsoft's Business Division Chief Stephen Elop laid out plans to launch the next version of Office with on-screen ads. Office users hated Clippy when he was trying to help; they are even less likely to welcome his presence once he turns into a salesman.

The success of iTunes and the iPhone App Store show that many customers are willing to support software development directly. Subtle or creative use of ads in iPhone apps and on the web show there are opportunities there, too. But the idea that ads can fund everything and that "more ads mean more money" has clearly been proven wrong in trial after trial.

On the Zune HD, Microsoft is likely to scare away more customers with its heavy-handed advertising that it can possibly attract with a handful of free adware-supported games.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic