Apple criticized for iPod shuffle's new 'authentication chip'

The matter drew considerable attention after iLounge reported in its review of the petite player that Apple was doing something "sneaky and arguably terrible for consumers" because "the only third-party headphones that will work are ones that haven’t even entered manufacturing yet, because they’ll need to contain yet another new Apple authentication chip, which will add to their price."

For its part, Apple says a variety of manufacturers will soon be releasing control-integrated headphones compatible with the new iPod shuffle, as well as adapters that provide playback controls that will work with any standard headphones. So the alternative argument is that rather than being sneaky, the iPod shuffle's playback controls are actually a new improvement over previous iPod systems, meaning that existing control-integrated headphones simply don't support all of its new features.

The evolution of iPod remote controls

Apple first introduced headphones with integrated playback controls with the 2007 iPhone; previous iPods had shipped with a clunky remote extension dongle that could be used with any standard headphones. The iPhone's new integrated switch allowed users to pause and start playback as well as accept or ignore incoming calls during playback. It uses a fourth conductor on the headphone jack to relay the signals from the switch to the unit, a feature Apple has patented. That extra pin is also used for the iPhone's mic.

Other smartphone manufacturers continue to use an external dongle to support remote controls, similar to the original generation of the iPod, which used an additional four pin port next to the the headphone jack to accept remote control signals.

Last fall, the new crop of iPods additionally gained integrated volume controls as well as a playback control switch. In addition to starting and pausing playback, the switch was also designed to support double-clicks and triple-clicks to step ahead or back one song or chapter in the currently playing track. That feature is also supported (although apparently not publicized) on the iPhone. With the conversion to using a four pin headphone jack to support mic and control signals, Apple also removed headphone jack video-output features on the new iPods, moving all video output to the Dock Connector instead.

The first generation iPod touch does not support the integrated playback controls nor mic recording because it lacks the fourth pin on its headphone jack. The current second generation touch does support both remote playback and audio recording features, just like the revised iPod classic and the new iPod nano. New unibody MacBooks released last fall also began supporting the new playback controls and mic input, thanks to their new iPhone-style four pin headphone jack.

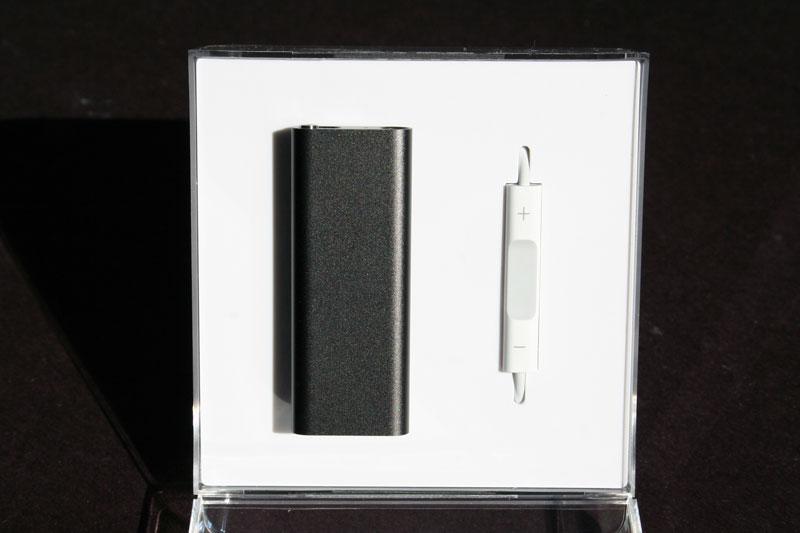

The latest iPod shuffle has added a new wrinkle of remote control features: double-click and hold or triple-click and hold to fast forward or rewind the currently playing track, as well as click and hold controls to manage playlist playback. The new player needed expanded remote controls because the device is designed without any other buttons on the unit itself; it also lacks any display, relying on an audio Voice Over navigation and the integrated controls instead.

The new click and hold controls on the third generation iPod shuffle do not work on previous models, and existing headphones designed to control the iPhone and previous iPod models do not support sending the signal that the new shuffle uses to indicate that the button is being held down. The iPod shuffle also implements full USB signaling over the four pin headphone jack instead of using a separate USB port, allowing the device to do everything (sync, charge, control, and play audio out) using just one external connector. It does not support audio recording, however.

Conspiracy to commit innovation?

In its widely publicized review, iLounge noted that "Apple has not announced replacement earphones for the shuffle, for whatever reason," but added that "it can be controlled by the Apple Earphones with Remote and Mic and In-Ear Headphones with Remote and Mic, but aggravatingly, not by Apple’s iPhone Stereo Headphones or other one-button headphones that were previously released."

That's because the single button control used on the iPhone's headphones offers no volume controls, and apparently was also not designed to support click and hold signals used on the new shuffle that was still under development at the time. However, the same review saw the limitation in a different light and suggested: "This just appears to be another Apple trick to randomly break compatibility with pre-existing accessories that might have been semi-useful, but didn’t contain its chips."

The Electronic Frontier Foundation was among the industry watchers who sided with iLounge on the matter, chastising Apple for "continuing to add more DRM to its own hardware [...] even as it attacks DRM on music."

But DRM, or "digital rights management," can be seen as multi-purpose. It has allowed content creators and hardware makers to decide how their products will be used. This includes efforts to use DRM to limit piracy, as Apple has successfully done within iTunes, but is not the only use of DRM.

Apple is not against DRM

Without initial DRM piracy controls on music, Apple would not have been able to resell the labels' music digitally, nor sell or rent studios' movies, nor stoke the blockbuster success of mobile software sales in the App Store. At the same time however, Apple resisted the studios' demands for continued DRM on music, not because of an ideological rejection of DRM, because the studios were also selling their music without DRM on CD.

Apple found it difficult to maintain its contractual obligations to police its FairPlay DRM system for music, but more importantly such work was completely pointless anyway because all the music Apple was reselling was already available from the studios on easy to rip, DRM-free CDs. In contrast, digital movies have never been sold by the studios in DRM-free formats, making the sale and rental of DRM-protected digital video (and the expectation that Apple maintain its video DRM) justifiable.

It still took Apple over half a decade to convince the music labels to sell their tracks through iTunes without DRM. That shift only happened once Apple could prove that it could create an audience of DRM music buyers. The shift to DRM-free music that Apple called for only ever happened once every other effort to sell DRM-protected music formats had failed, from SACD and DVD-audio discs; to Microsoft's PlaysForSure to Zune DRM; to subscription music DRM from Real Networks and others.

The Demonizing of DRM

Apple has never "attacked DRM" in principle in the sense that many free software advocates do. DRM only acts as a security mechanism for reinforcing a particular business model. When designed only to serve the needs of content providers, DRM has historically failed. Sony's ATRAC DRM on MiniDiscs and its digital WalkMan players and Microsoft's PlaysForSure, WMA, and WMV formats, along with other attempts to create producer-friendly but customer-hostile DRM systems, have all failed in the market after being rejected by consumers.

When developed to serve the needs of both consumers and producers, DRM has proven wildly effective and creating functional markets. Apple's iTunes found success where no other music store could using minimally invasive FairPlay DRM. It replicated the same success in TV and movie content and again in mobile software with iPod games and later the iPhone App Store. Audible's use of DRM for audiobooks, Amazon's use of DRM for digital Kindle ebooks, and the DRM used in video games from every console maker from Nintendo's DS and Wii to Sony's PlayStations to Microsoft's Xbox line are similarly intended to create viable markets in those product categories.

Without the protections of DRM, widespread piracy would have eroded the ability of a real market for audio, video, and mobile software from ever developing. Previous attempts to distribute commercial digital content without any security (such as eMusic, YouTube, and sites selling mobile software) have failed to gain any significant support from the major content producers and developers. Apple's neutral stance as a mediator between producers and consumers has given it the ability to design DRM systems that work for both sides.

Outside of the recent attempt by the music labels to sell their music as MP3s through Amazon, which was entirely an effort to gain some leverage against Apple's successful, established iTunes business, content producers have always worked to protect their assets from widespread piracy in anyway possible. That makes the ideological demand to drop DRM fanciful at best and detrimental to the survival of fair, functional digital download markets like iTunes at worst.

What about Hardware DRM?

With every viable digital download software market taking its success upon DRM, hardware makers have also taken to DRM to protect business models. Fearing that hardware could be used to bypass the DRM protections in HD video formats from BluRay to digital download rentals and purchases, the industry has worked to build end-to-end security models to prevent the full quality export of video signals played from DRM-protected sources.

In the past, physical analogs to DRM have acted to inhibit widespread piracy. Until the late 90s, audio CDs were simply impossible to rip and compress down into digital files in a way that could be widely distributed, making the plastic discs a sort of hardware security dongle themselves. While users could transfer music from CD to tape, the loss in quality left CD sales protected from widespread assault. However, once it became possible for a single user to mass duplicate music from a CD to hundreds of thousands of file sharing "friends" at the same pristine digital quality, the music industry scrambled to find a way to protect its content from effortless mass piracy.

Most of those efforts failed because the Pandora's Box had already been opened. Studios have similarly worked to prevent the same widespread duplication of content from destroying the video business. In order to license HD movies for resale and rental, Apple has had to add industry-standard hardware DRM protection to its devices, from the HDMI digital video output on the Apple TV to the Dock Connector ports on its iPods to the new Mini DisplayPort on its Mac desktops and notebooks. Unless connected to a secured video display, these machines may refuse to output a full quality signal when playing commercial HD video. BluRay devices are similarly required to support hardware DRM security in order to license playback of the format (as did the failed HD-DVD format).

Do new iPod headphones use DRM?

In addition to protecting HD video content, Apple also uses proprietary video signaling on recent iPods to enforce its ability to license "Made for iPod" accessories. The EFF and iLounge may be operating under the assumption Apple is similarly using the new iPod shuffle controls as a way to force manufacturers to pay licensing fees in order to build compatible control-integrated replacement headphones.

iLounge described this as a "nightmare scenario," "a world in which Apple controls and taxes literally every piece of the iPod purchase from headphones to chargers, jacking up their prices, forcing customers to re-purchase things they already own, while making only marginal improvements in their functionality." The EFF similarly charged Apple with "impeding competition and innovation."

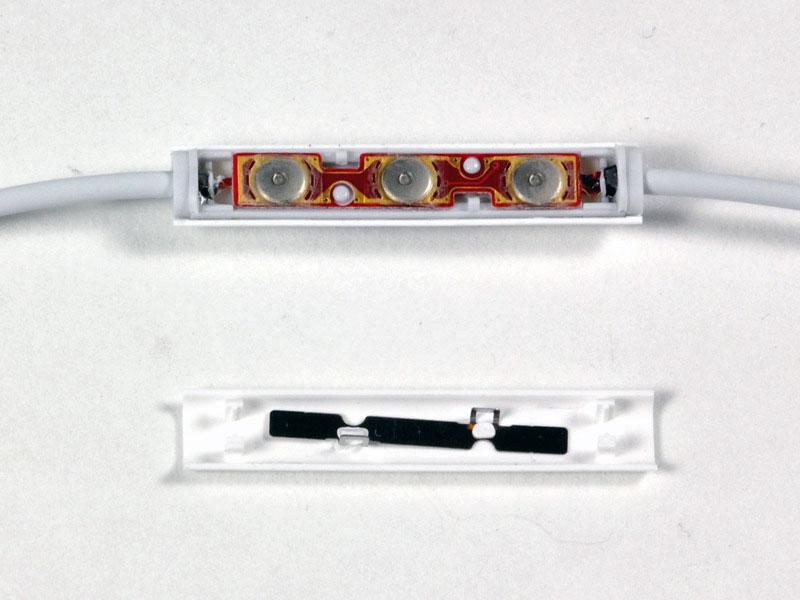

The controverisal chip reportedly sits behind these buttons in the shuffle's third-gen earphones | Source: iFixIt

The claim that the new iPod shuffle uses DRM to prevent third party compatibility has not been established as fact by Apple or from reputable sources, however. Update: a Macworld article by Dan Frakes cites an Apple spokesman as saying, "As part of the Made for iPod program, we make sure that third party headphones work properly with the third generation iPod shuffle." The article also states, "however, there is no DRM in this new control chip, according to Monster Cable's Kevin Lee, who added, 'In fact, it's not even authentication. It just gives us a way to control the iPod.'"

If it indeed uses some new proprietary signaling to preclude replacement by unlicensed, knockoff headphone makers, the worst case scenario, as iLounge describes, is that users will have to either buy Apple or Apple-authorized headphones to control the unit, or alternatively buy a remote control adapter, much the same way as nearly every smartphone on the market (apart from the iPhone) requires a nonstandard adapter to use regular headphones.

Again, the alternative argument to Apple stifling competition is that the company has decided in some instances to sacrifice backwards compatibility in order to achieve its success in a highly competitive environment with plenty of iPod shuffle alternatives, few barriers to competition, and very little real innovation outside of the iPod itself. The industry at large and knockoff manufacturers specifically have contributed next to nothing toward innovative design in headphones (from remote controls to mic integration), and few iPod shuffle users will be racing to dump the unit's included headphones for a cheaper pair than the simple earbuds that ship in the box.

That may leave fears of Apple's "DRMed headphones" entirely an issue for users with a favorite set of headphones, but without any interest in buying a remote control dongle for them, and yet an instance upon buying Apple's low end iPod, a corner case that doesn't seem worth much of this weekend's heated outrage.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic