An Introductory Mac OS X Leopard Review: Present & Future Value

Mac OS X Leopard delivers performance enhancements, new apps and features, and exposes new functionality for developers to exploit in their own applications. How much is that worth, and where does Mac OS X have to go in the future? In this final installment of our Leopard series, we offer a roundup of the value presented by Leopard, how it compares with Apple's previous efforts, and what users can expect over the next year of Leopard and into the future.

Back in the days of computers as large as rooms, there wasn't an obvious difference between hardware and software features. AT&T, Digital, IBM, and other major vendors commonly supplied integrated solutions, not just retail products for end users to assemble.

IBM monopolized the market for business computing, and AT&T monopolized the market for telecommunications in the US. That allowed them to set prices largely as they desired. The features of a system were targeted at the market's needs, with artificial boundaries between product offerings that allowed the major vendors to sell the same product at different price points, differentiated by the features disabled in software.

When the price IBM and AT&T demanded for their products began to exceed the work required to duplicate the functionality they offered, even users locked up in a monopolistic dungeon began to devise ways to create competition by building their own solutions. IBM fought to prevent other companies from selling parts for its systems; challengers even had to incorporate IBM's bugs into their products to ensure that IBM's software wouldn't refuse to work with their alternative hardware. AT&T fought BSDi in court to prevent an open source alternative to its commercial Unix. Neither of those efforts were able to preserve their monopoly positions.

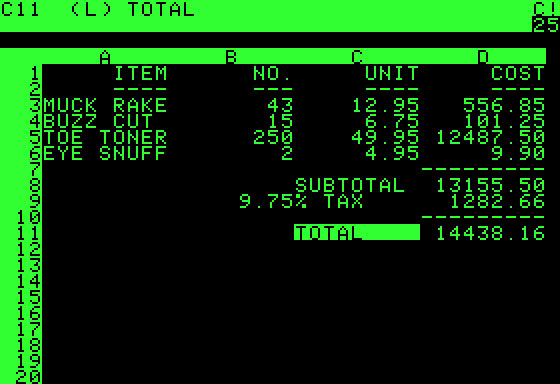

When microcomputers arrived in the late 70s, they quickly shifted from a novelty to a very valuable product once killer software applications arrived. Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston's new VisiCalc spreadsheet (below) for the Apple II ushered in the world of spreadsheets and boosted Apple's hardware sales dramatically. There were already much more powerful computers sold by IBM that allowed users to do the same kinds of things, but not for the $2000 price of the Apple II.

Value in Microcomputers

When Apple introduced the Lisa for $9,995, it impressed the critics but failed to gain much traction in the market because the value it offered was offset by the value it demanded. The Macintosh delivered much of the same features at a much lower price point in 1984, but after its novelty wore off, sales went flat. It wasn't until the value of desktop publishing was unlocked by the LaserWriter that Mac sales again went up in 1986. The addition of free tools such as HyperCard also increased the Mac's value.

However, rather than working to continually add value to the Mac, Apple increasingly sought to pull value from it. Apple CEO John Sculley and Mac product manager Jean-Luis Gassée didn't recognize the Mac environment as value to sell and improve upon, but rather as a privileged position for setting high minimum prices for its hardware offerings.

This was the same thing IBM and AT&T had done in the prior decade. The result was that a number of groups worked to duplicate the Mac desktop at lower cost (or to serve markets Apple didn't), resulting in the Atari ST, the Commodore Amiga, Berkeley System's GEOS, Digital Research's GEM/1, the Acorn Archimedes, IBM's OS/2 Presentation Manager, and Microsoft's Windows, as outlined in the article Office Wars 3.

Apple Learns About Value

Having only targeted the higher end of the creative market, Apple worked to provide value to its customers, delivering advancements in intuitive interfaces, simplified networking, and color and video technology into the early 90s. At the same time however, its market position declined to the point where Apple couldn't maintain the same pace without also matching the advances of competitors.

Apple attempted to continue in the same direction, introducing PowerTalk as an extension of AppleTalk to provide email and security services; QuickDraw GX to expand its graphics and print offerings into advanced typography; QuickDraw 3D (below) to support modeling; and extensions to HyperCard and QuickTime to fuel new multimedia applications. Those efforts all failed, largely because they didn't offer practical value at a price that could sustain their development, as noted in Platform Crisis: The Lazy Dinosaur.

At the same time, Apple had been developing Newton as a series of technology ideas for modern information appliances. Worried that Newton devices might eat into its existing Mac sales, Apple limited its potential by delivering it only as a PDA device. There was no major market for book-sized computers, so the value Apple invested and offered in the Newton found little payback in the market, as the article Newton Lessons for Apple's New Platform details.

Value at NeXT, Be

Starting in the late 80s, NeXT offered a parallel path of history alongside Apple. Worried that NeXT would compete directly against its Mac business, Apple pushed NeXT to agree to do its business in an even higher market tier. That resulted in a machine priced high enough to only really impact those who could afford to invest aggressively in technology. Other companies partnered with NeXT or licensed its technology, but then failed to do anything with it, including IBM, HP, Sun, and Digital.

Unlike Apple, NeXT found it could sell its software more effectively than an integrated hardware and software product. NeXT's software was portable and its hardware had no established market. Conversely, Apple's software wasn't very portable, but it did have significant established users in education and creative markets. Apple could easily ask a premium price for its hardware because of its free software, while NeXT had to sell its software at a significant premium because it couldn't sell hardware.

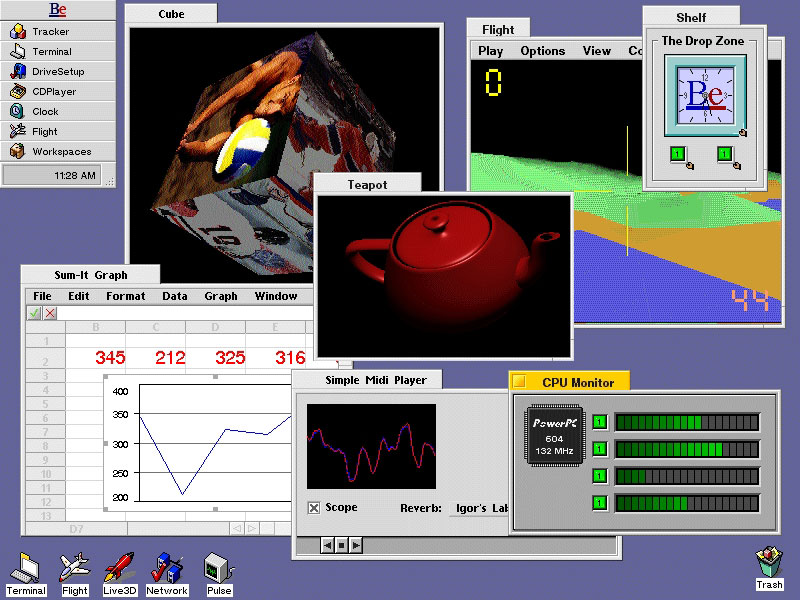

When Gassée and early Newton developer Steve Sakoman left Apple to start Be Inc., in 1990, they similarly developed software with value tied to hardware that could not be sold outside of a very narrow niche. Unlike NeXT, Be couldn't deliver its BeOS software (below) in the market, as there was absolutely no market for alternative operating systems by the mid 90s. The company ended up being sold off to Palm, and a variety of its core talent— including Sakoman and file system developer Dominic Giampaolo— ended up at Apple.

Refocusing on Value

Rather than just continuing to deliver new products that added features, Apple in 1997 began a revaluation of what value it was really adding. Projects including QuickDraw GX and PowerTalk were evaluated for usable components, but their overall architectures were discarded. Independent efforts such as QuickDraw 3D were abandoned in favor of industry supported standards such as OpenGL.

After doing little to incorporate real value into the Mac operating system since System 7 first appeared in 1991, the new Apple released a series of updates that folded in stripped down, practical functionality devoid of the grandiose pretense of its early 90s projects. It also balanced the value it invested by asking for value back, making the Mac OS a retail product sold at regular reference releases, with free updates offered in between.

IBM and Microsoft had been selling their PC software for around $200 since the late 80s; Apple's Mac System Software was largely considered to be a free product until 1997. Since then, Apple has marketed substantial features that add obvious value into its reference releases, which enables the company to invest major resources into research and development without an uncertain payback for its work.

On page 2 of 2: The Compounding Value of Mac OS X; Mac OS X 10.0 Cheetah; Mac OS X 10.1 Puma; Mac OS 10.2 Jaguar; Mac OS X 10.3 Panther; Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger; Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard; The Future of Mac OS X; and Leopard Gets An A.

After plotting out a new course to retake education, target consumers, and expand into professional and prosumer creative markets, Apple began delivering Mac OS X releases in 2001.

Mac OS X 10.0 Cheetah (above) demonstrated a lot of potential but had limited mainstream appeal; existing Mac applications didn't yet take advantage of its new Quartz graphics engine, which was actually slower than the classic Mac OS 9. Applications that made use of QuickDraw 3D weren't supported and couldn't just substitute OpenGL. However, the new system did allow Mac hardware to run Unix code, and it could run the classic Mac OS environment in a compatibility box about as fast as it ran solo, thanks to OS X's low level improvements, including virtual memory.

Mac OS X 10.1 Puma (above) was a free update that solved some problems of the initial commercial offering, and added some features the system was missing over the classic Mac OS, including DVD playback. Much of the value in Mac OS X was still untapped potential, and much of the improvements centered around integration with Mac OS 9. Mac OS X received an additional seven free updates leading up to the next reference release.

Mac OS 10.2 Jaguar (above) in 2002 could officially "bury" the corpse of Mac OS 9, devoting Apple's entire efforts into a single operating system product. It offered major advances in speed that made the system usable for a broad audience. It also added support for Bonjour (then called Rendezvous), an implementation of AppleTalk networking features that extracted their value to run over standard Internet Protocol networks.

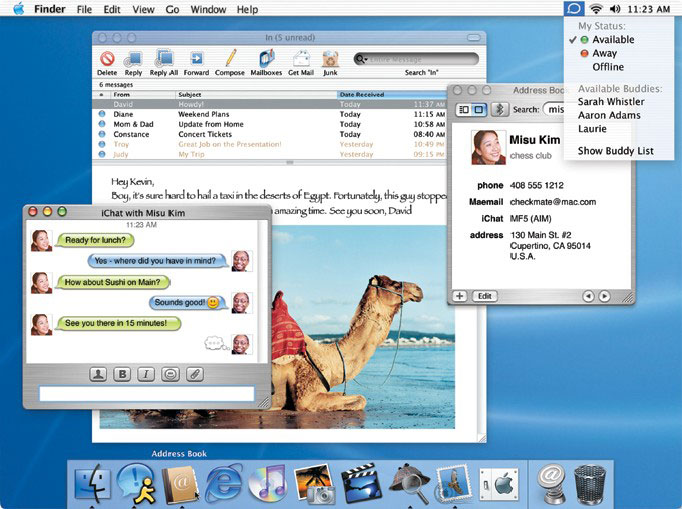

Jaguar bundled Ink services from Newton, and adopted the open source Common Unix Printing System to streamline and standardize its printer device support. It added new and revised applications, such as iChat, the revamped Finder, and shortly after its initial release, it also bundled the free iCal. Jaguar was updated eight times after its release.

Mac OS X 10.3 Panther (above) delivered major new value in a series of more flashy features, including Fast User Switching, Exposé, and the new iChat AV for video conferencing. It also revised the overall look and made numerous usability improvements, including support for file archives, fax support, security features such as FileVault, and revised its developer tools under the name Xcode. Panther was updated nine times for free after its release.

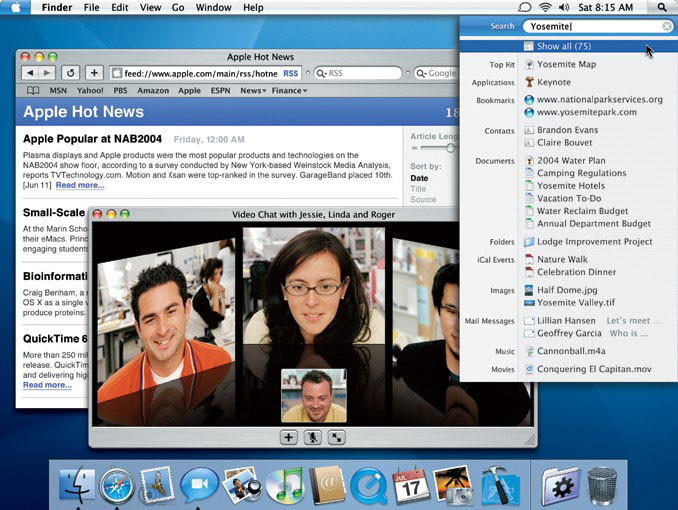

Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger (above, an early developer preview from WWDC 2004) introduced even more marketing features for its reference release: Spotlight searching paired Apple's existing V-Twin search technology with file system metadata indexing ideas inspired by the BeOS. Dashboard expanded upon the concept of Exposé to add a new widget environment.

The VoiceOver screen reader expanded upon Mac OS X's existing accessibility features, and Automator made it easier to setup simple workflows or to use complex AppleScript in more sophisticated ways. Apple added support for RSS syndication, enabling website feed parsing in Safari, podcasting support in iTunes, and photocasting support in iPhoto.

Entirely new plumbing in QuickTime 7 delivered major advances in compression for users, improving iChat and movie playback while also enabling Apple to expand its moves into broadcasting and content markets with its Pro Apps.

Tiger developments also accommodated the move to Intel processors. It has been updated ten times since its release.

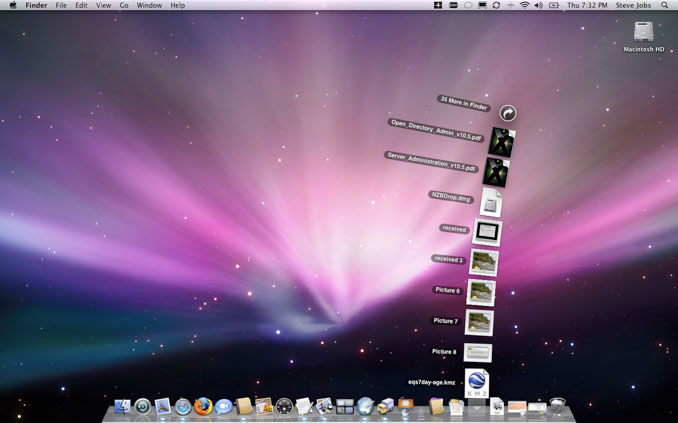

Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard similarly added lots of new marketing features while also adding new potential value for developers to unlock. Time Machine isn't just file backups, its a way to manage changes within collections back through time and perform system queries at dates in the past. Spaces isn't just a virtual desktop, but also integrates into Exposé, making it far more assessable to non-technical users.

Without following Apple's marketing names, it's sometimes difficult to describe where one feature beings and another ends. Enhancements to Core Video and Core Graphics benefit overall operations, QuickTime and iChat specifically; iChat Theater incorporates Screen Sharing and Quick Look features to distribute views of documents. Mail, iChat, Address Book, and iCal all integrate in ways that make them more useful than just single applications, but the design behind these apps doesn't limit users just to what Apple provides. An improved chat, contacts, or calendar client can take advantage of the underlying system-wide calendar store, contacts, or Core Image effects to provide alternatives that build upon what Apple bundles. Every new or expanded feature adds value not just in itself, but throughout the entire system in ways that benefits lots of applications and enables future developments.

On the server side, Apple has moved beyond just offering Mac OS X Server as a platform for running Unix server applications with a nice user interface; Leopard Server introduces a set of significant new advances with the internally designed iCal Server, Wiki Server, and Podcast Producer, all of which are designed to make Apple's hardware more attractive to educational and corporate users.

The Future of Mac OS X

Is there any room left for Mac OS X 10.6? Steve Jobs noted in a recent interview that Apple plans to keep its development pace of Mac OS X going at around an 18 month schedule. That makes it likely that 10.6 will be demonstrated at next summer's WWDC, and released in early 2009.

Expect Apple to evolve its user interface, with a focus on behavior rather than just appearance. While desktop Macs are unlikely to get touch screens, subcompact new portable systems that sit between the iPhone and the MacBook in Apple's product lineup may be the first devices to really use resolution independence in a desktop-oriented environment, shifting from a mouse pointer and windows to an interactive touch interface closer to the iPhone's.

Users in a desktop environment are less likely to give up the efficiently of the pointer, so new standardized conventions that minimize the interface to focus on data are likely to appear. Safari already banishes the majority of the menu bar to direct attention on its web page content. More context sensitive controls like those presented in iWork applications are also likely to find wider adoption.

Larger displays will at some point demand a replacement of the standard menu bar with a solution that allows the user to call up menu functions without making a pointer pilgrimage to the top of one of their displays. More context sensitive options for these commands may help, or even an Exposé mode that exposes menu bar functions (and the underutilized Services hidden away in the application menu) with a hot key or a mouse gesture. New plugin architectures could help to solve problems such as document format conversions, or add new file views to the Finder. And how about a rotating Dock to allow the user to select from sets of applications and Stacks related to the given task?

Leopard Gets An A

It's easy to invent new ideas for Mac OS X because everything in the system is already designed to work together cohesively. It's not a mishmash of old and new tied to lots of closed legacy ideas, but a continually renewed set of interface concepts designed to make features accessible, using open existing implementations as much as possible.

Leopard easily delivers more value to the Mac than any previous release. That makes it interesting to see what Apple will do for an encore. Over the next year, buyers can also expect regular improvements delivered for free about every six weeks. With Apple now selling twice as many Macs in a quarter compared to 2005, and nearly three times as many as it sold per quarter in 2004, Leopard should get a quick reception among new Mac users. It should also grab a lot of new interest in the Mac platform, both from consumers and in business markets that see the value Apple offers.

Check out earlier installments of our Leopard Review Series:

Also check out our earlier Road to Leopard series:

Where to Buy

Leopard can be purchased from online retailer Amazon.com, which does not charge sales tax and is offering an instant $20 off Leopard single license and $10 off the family pack, bringing the costs down to $109, and $189, respectively. Amazon is also offering deals on Leopard Server.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele and Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher